The GWSB Expertise Series

GWSB Expertise is a series of short articles on topical issues written by the George Washington University School of Business (GWSB) faculty. This week, Dr. Katina Sawyer discusses her research on workplace discrimination against transgender employees and how employers can foster more inclusive workplace cultures.

While recent legislation has ruled that sexual orientation and gender identity are now protected classes under Title VII, we know from past precedent that making discrimination illegal doesn’t fully eliminate bias at work. This is because biases can manifest in more subtle ways than what the law can accurately account for.

For example, 77% of transgender employees report taking active steps to avoid mistreatment at work, given they also report facing high levels of formal (67%) and informal (25%) discrimination at work. While it is now illegal to fire someone just because of their gender identity, more subtle, informal discrimination may be difficult to detect at work.

In my own work, published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, my colleagues and I found that 47% of trans employees experienced at least some discriminatory behavior on a daily basis at work — mostly covert — such as feeling forced to act in traditionally gendered ways, being ostracized, or being subject to transphobic remarks. Thus, in order to create truly inclusive workplaces, employers need to change their culture as well as their policies.

In our recent publication within the Harvard Business Review magazine, my collaborators and I provide some tips for how to create trans inclusive workplaces. Broadly, adopting trans inclusive policies is just the start of changing workplace cultures to be more inclusive of trans employees. Supporting gender transitions, developing trans-specific diversity training, and implementing resiliency interventions can also promote a more inclusive workplace. Further, our recent work published in the Journal of Applied Psychology demonstrates the power of coworkers who take risks to stand up for trans justice in the workplace. For more information on how to make your workplace more trans-inclusive, listen to my Harvard Business Review Ideacast episode on this topic.

Previous Articles

Build Your Expertise

- The Resiliency of the Hospitality Industry - Dr. Larry Yu

-

Leisure travel is a part of our culture and a way of life. Travel for business and conventions are essential business activities.

However, the hospitality business is most vulnerable to any major external shocks which are beyond the control of the owners and managers, the COVID-19 pandemic halted almost completely the mobility of people for business and leisure purposes.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has since devastated the hospitality industry in the U.S.:

- Eight in 10 hotel rooms empty

- 70 percent of hotel employees laid off or furloughed

- $400 million lost in room revenue every day

However, the hospitality business has shown its resilience when facing major crises in the past and it always bounced back with new innovative operations to address consumers’ concerns and expectations.

There are now signs of recovery for the hospitality business in other countries, primarily driven by local demand. There is a glimmer of hope for the hospitality business in the U.S. This is a time to plan for post-pandemic reopening as consumers’ expectations for hospitality services and behaviors will change to a certain extent, particularly consumers’ heightened expectations for safety and cleanliness protocols, amenities and standards. Hotel organizations have proactively implemented safety and cleanliness initiatives, including Hilton’s CleanStay, Commitment to Clean guided by Marriott Global Cleanliness Council, Global Care & Cleanliness Commitment by Hyatt, and Airbnb’s Cleaning Protocol Certification program for hosts. Airlines, such as Delta (Safe & Healthy Flying) and United (CleanPlus), have initiated safety and cleanliness programs to provide a healthy travel experience.

Furthermore, the first wave of demand will be driven by local and regional consumers. An actionable plan supported by management innovations will position hospitality organizations competitively in the post-pandemic market, such as the Pay-What-You-Can campaign to promote in-state travel by independent hotel and tour operators in Maine and the Press Play campaign by the Shreveport-Bossier Convention and Tourism Bureau in Louisiana to promote “nearcations” by locals and regional road trips by auto travel.

- Why Employees Can React Negatively to COVID-19 Initiatives - Dr. Herman Aguinis

-

Amazon, Kroger, GW, and many organizations are implementing corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives to try to do the right thing during the COVID-19 pandemic. That is, they are focusing not just on financial results, but on the three “P’s” simultaneously: profits, people, and planet. Consider the case of Amazon, which drastically expanded online grocery delivery to provide an essential service for individuals affected by the pandemic. However, with the increased need for fulfillment centers to run smoothly and at full capacity, Amazon began facing backlash from its own employees who protested unsafe conditions such as not having adequate protective equipment.

From the perspective of employees, Amazon’s well-designed and socially responsible initiative required too much of them and, therefore, had negative effects on employees’ attitudes and performance — the opposite of what Amazon had intended! Our research adopting a behavioral perspective helps us understand why, when, and how well-intended CSR initiatives, such as the ones implemented by Amazon, can lead to desired positive outcomes or, on the other hand, unintended negative consequences.

Our research shows that the way employees perceive and react to CSR policies and initiatives are key determinants of how they are implemented and their ultimate success or failure. For example, responses to COVID-19 are more likely to succeed if they involve employee input (as opposed to being mandated by management top-down), are genuine (not just greenwashing), and part of an organization’s long-term strategy (as opposed to a tangential or peripheral temporary action).

A behavioral perspective allows us to understand that when firms do things right, top-performing employees are more engaged, satisfied, committed to their organizations, and less likely to leave. And, it is precisely these top-performing employees who will help companies to emerge from this crisis. Certainly, the last thing a company can afford now is for their best employees to leave as soon as opportunities become available.

- The Pandemic and Its Consequences (Part 1) - Dr. Danny Leipziger

-

The last decade has seen several dramatic shifts in the global economic landscape. While many following the global financial crisis were negative, but there were also some bright spots. Much of the optimism revolved around Emerging Market Economies (EMEs), where the number of people below the poverty line of subsistence had fallen dramatically. And despite low commodity prices and demographic pressures, many were able to borrow on the world’s capital markets, taking advantage of historically low interest rates. Even the rising of protectionist sentiments, stoked by the U.S.-China trade war, was not the spark leading to a reversal of fortunes. But COVID-19 was.

The pandemic caused a reversal of $100 billion of capital from EMEs in the first three months of 2020 alone and cut off an equal amount of remittances normally destined for developing countries. This shock, added to the global downturn in GDP that will average more than 5-6 percent in most advanced economies this year, will undoubtedly harm EMEs who are less resilient and have fewer resources on which to draw. The EMEs will see years of past development gains eroded, and poverty rates will inevitably rise.

One major area of concern is their external indebtedness. This has prompted calls for debt relief and debt forgiveness for EMEs; it has forced the international financial institutions to mobilize more than $1 trillion in relief funds; and it has forced most countries to spend more at a time when they are exporting less, receiving less capital, and are facing larger fiscal deficits. Unlike the U.S., they cannot simply print their way out of distress.

While it is natural for policymakers to worry first about their surging levels of unemployment and their crumbling small business sectors, the pandemic’s effects in less fortunate parts of the world, should not be overlooked. As the pandemic illustrates, countries are still deeply connected, and the actions to deal only with national concerns will eventually reverberate back. Global cooperation, therefore, needs to be bolstered quickly and effectively, in order to protect us all.

- The Pandemic and Its Consequences (Part 2) - Dr. Danny Leipziger

-

The COVID-19 pandemic is driving a global economic “reversal of fortunes,” while at the same time underscoring the inextricable interconnectivity of the 21st century global economy. Policymakers do need to first focus on domestic economic concerns, but they ignore the pandemic’s impact in the rest of the world at their own eventual peril.

Already confronted with dramatic changes in global value chains, a new shift towards self-reliance, re-shoring of production and jobs, the raising of tariffs, and the repatriation of capital can only induce a longer and deeper recession. Looking at what the pandemic has done to global travel and tourism exemplifies the risks to the world economy of autarkic tendencies.

If inventory management and self-reliance dominate, the progress of the past 30 years in terms shared growth and poverty reduction will be reversed. If governments cannot manage their debts because global growth is stymied, it will simply exacerbate debt distress in poorer countries and cause permanent declines in income of disadvantaged groups in richer countries. And if cold-war policies between the world’s two largest economies continue unabated, countries will increasingly feel isolated and abandoned.

A renewed and revised common understanding is required at this critical moment. The G-20 would be well advised to try and seek such consensus, to head off new trade pressures and calls for inward-looking policies, and to restore a greater sense of common purpose and international cooperation, and to deal with inevitable debt defaults among Emerging Market Economies. The places to start are not only the global health crisis, but also the worst economic crisis in almost 100 years. Continuing lack of common purpose, uncertainty, and fragmentation of efforts will only serve to harm all concerned.

- Washington Redskins Name Change: The Time Is NOW - Dr. Lisa Delpy Neirotti

-

Although initial calls for changing the Redskins name date back 40 years, the recent pressure ignited by the George Floyd’s killing is different. With minority owners looking to sell their 40 percent of the team, major sponsors such as FedEx, Pepsi and Bank of America threatening to pull out, and Amazon, Nike, Walmart and others removing Redskin merchandise, the time has come for change.

The once adamant team owner, Dan Snyder — who has stated the name will “never” change — has conceded to a review which is expected to result in a new team name and mascot. Some speculate that the team colors of burgundy and gold will remain, with the name continuing to include “Red” such as “Redhawks” or “Redtails.” Others support Washington Warriors despite the name already used by the NBA Golden State Warriors. Another option is to develop a completely new name and look, one that will appeal to a young, future fan. Perhaps review some esport teams’ creative and edgy logos. Ultimately brand experts consider team heritage, how the name will resonate with local residents, sponsors, and does it pass social-political tests?

The NHL San Jose Sharks broke the mold when they included the color teal in their logo despite skepticism, ultimately generating 25 percent of NHL merchandise during the franchise’s first two years. It’s time the Redskins look forward, not back and lead the NFL into the future.

Considering the sweeping changes resulting from COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement, coupled with the fact that the Redskins have a new coach and general manager, and a new stadium around the corner, now is a good transition time for a bold re-branding. Furthermore, the Redskins have seen the least growth of any NFL team in the last five years in both franchise valuation and operating income, and a brand refresh is needed.

Although the team announced a name change in early July, for this year it will simply be referred to as the “Washington Football Team,” considering that a proper re-branding takes 18 to 24 months. The process involves market research studies, trademark reviews, development of visual identities, television tests, plus time to change out signage, stationary, promotional items, digital assets, and more at a cost up to $3 million. This price is small, however, compared to the amount the team will continue to lose if change is not made.

- How Does Humanity Respond to Slow Onset Disasters? - Dr. Jorge Rivera

-

Why have there been delays and reversals in responding to COVID-19? Research that I jointly conducted with Viviane Clement and Peter Tashman on adaptation to climate change’s gradual effects can shed some light. We found that official responses to slow-onset natural disasters tend to follow patterns where the impending acute effects are initially unsuspected — or worse, ignored.

During its early stages, COVID-19 generated apathy and was even characterized as a “hoax.” As the severity of a disaster’s effects becomes harder to ignore, the adoption of initially avoided easy responses increases. Unfortunately, as consequences become severe, they overwhelm societies’ ability to respond, forcing retreat and, in the most extreme cases, collapse and widespread deaths.

There are several reasons this response pattern arises:

- Facing an emerging disaster, most top decision makers are oblivious to gradual cues, and those that are aware find it difficult to overcome strong social/political/economic inertial forces that favor the status quo. Even if detected, these slow-onset disaster cues are not seen as posing a strong enough threat to gain enough attention and catalyze proactive responses.

- During the medium-severity stages of slow onset natural disasters, the highest response levels are observed because the adverse effects are moderate enough to render response efforts effective and cost effective. These increased response levels may also arise from opportunities to imitate and/or collaborate with others that have already adopted successful and innovative responses.

- At the other extreme, when facing severe disasters, decision makers’ heightened vulnerability enhances their support for aggressive responses. Despite this, societies tend to begin abandoning their willingness to respond when facing extreme disaster adversity.

This is because of a reliance on traditional responses whose effectiveness is undermined by the severity of the disaster. Additionally, citizens and organizations show increasing levels of response fatigue, limiting their ability to sustain high alert to the disaster. This fatigue stage is where we are in the U.S. now, with millions going back to “normal” despite the lack a cure for the pandemic.

- Self-Improvement in the Age of COVID-19 - Dr. Christopher Kayes and Dr. Philip W. Wirtz

-

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in times of extreme anxiety, financial hardship and a health crisis. The impact is psychological and challenging, but many individuals have found that these uncertain times provide a unique opportunity for self-improvement. Home improvement, taking up running, learning to code in Python, or (even more relevant) starting a new degree or certificate program are just a few of the types of diverse self-improvement activities that we have seen. These activities are more than just fun; research has shown they support improved happiness, health, sleep and reduced stress.

Over the past few years, we’ve been studying the psychological factors associated with making progress in self-improvement efforts. Our research is focused on how to overcome the inevitable frustrations that may be stifling progress and leading us to stop short of our goals. We identified a number of factors associated with improvement, but three stand out as most important during the current crisis.

Positive emotional engagement. Exciting, interesting and curious — these are words that people rank among the highest when they are improving. For example, find a way to make your newly acquired skill of coding relevant to your work or interests, not an abstract process of memorizing code.

Creative problem solving. People show a greater likelihood of learning and growing when they are improving. They find multiple ways to engage in the activity — for example, not just getting a better time in running that mile, but supplementing their experience by reading about Roger Bannister and how he became the first person to break the 4-minute mile.

Small progress. Our research shows progress isn’t always swift or dramatic. Small, consistent gains in ability are achieved by making progress each day toward new levels of incremental improvement. Start by replacing your bathroom floor before deciding to replace your kitchen cabinets.

Self-improvement efforts are flourishing. With seemingly constant flow of bad news, people around the globe are seeking to improve career skills, cultivate hobbies, or pursue goals such as a long sought-after graduate degree.

- Planning for the Next Pandemic (Part 1) - Dr. Ernest Forman

-

Planning and allocating resources for the next pandemic is an obvious thing to do. But if we don’t begin to do it now, it will be difficult to overcome the human tendency for decision makers to gamble on the next pandemic not happening in their lifetime rather than spend $10 to $20 billion now.

Why is this the case?

Kahneman and Tversky, in their work Prospect Theory, which was cited in Kahneman’s Nobel Prize, showed that because the utility curve for losses is steeper than for gains, humans are risk-averse when it comes to gains, but risk-seeking when it comes to losses. The significance of this is that humans would rather gamble on risks not occurring than invest today’s money/resources in reducing risks that may never happen.

• The mayor of Houston gambled when he refused, year after year, to invest about $30 million to fix the levies. The subsequent damage from Hurricane Harvey was estimated to be about $30 billion.

• Bill Gates cited an independent international commission estimate that it would have taken at least $4.5 billion a year to protect against pandemics. Today, that amount is dwarfed by the economic (in the tens of trillions of dollars) and human toll of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In retrospect, it should have been obvious to the mayor of Houston as well as our governmental planners for pandemic risk that an ounce of prevention would have been worth much more than a pound of cure. But that doesn’t mean that tomorrow’s planners and leaders will feel the same about future risks, including the next pandemic. For one thing, our memories are short — and political positions are difficult to change.

- Planning for the Next Pandemic (Part 2) - Dr. Ernest Forman

-

It’s difficult to convince decision makers to invest in reducing risks, any one of them which may never happen (but according to the law of large numbers, on the average some will). Without some way to quantify the risks and benefits of investing today to reduce risks in the future, it is impossible to demonstrate in a convincing way that an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure. It is too easy to dismiss arguments based on analogies to past events, or qualitative arguments, or even quantitative arguments that are not comprehensive or scientifically valid.

Quantitative analytics that are comprehensive and scientifically valid are required to convince decision makers to invest in reducing risks for events that may never happen. After all, it isn’t always true that an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure. The “worth” must be based on comprehensive, scientifically valid quantified estimates of the likelihoods, impacts and costs to control risks.

In an April 2020 article in Brinknews, Mark Trexler wrote: “The problem with COVID-19 has not been a lack of dedication and expertise among health professionals; rather, it’s the chronic shortfall in the political and budgetary prioritization of pandemic preparedness. Such preparedness need not have been overly costly; by one estimate, the global cost of being prepared for a pandemic like COVID-19 works out to $1-2 per person. That’s a trivial amount, in hindsight.”

In order to address the shortfall in the political and budgetary prioritization of pandemic preparedness, improved risk analytics are required to identify specific risks, estimate their likelihoods and impacts, using both data as well as human judgment, and in a comprehensive, scientifically valid process.

Such a process has been in development for the past six years and is now available to help guide decision making bodies in arriving at sound, defensible decisions when planning for the future pandemics. If you are interested in learning more, consider Professor Forman’s Risk Management course.

- Why Safety Is More Important Now Than Ever - Dr. James Bailey

-

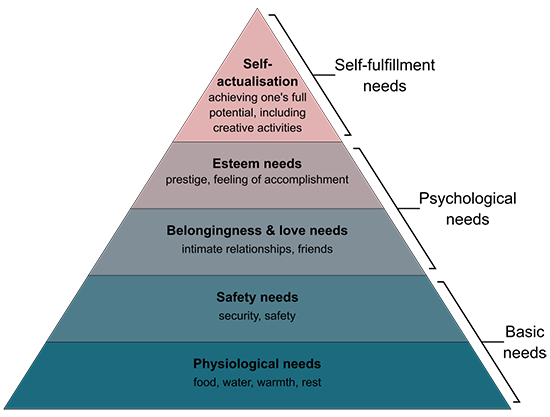

Almost everyone has heard of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. It is a universal system of human striving, depicted as a pyramid with basic needs leading to psychological ones before reaching transcendent self-fulfillment. It’s a vital prism for refracting human experience that has stood the test of time. It’s well known because it’s true.

And, it reminds us that although we may have scaled the side, we can just as easily slide down it.

Just a few months ago America was at record low unemployment and record high stock markets. Basic needs — physiological and safety — were givens. The vast majority of Americans were looking for love and confidence (psychological) while a lucky few were actualizing (self-fulfillment needs).

Clang. Crash. Crack. COVID.

In a mere matter of months, 330 million Americans went from reconciling their psychological needs or realizing their self-fulfillment needs to distressing about their basic needs. Collectively, we’ve tumbled down the steep slope. We’re back to the basics.

People are scared. The business word for scared is “stressed.” Research shows that highly stressed people perform poorly in almost every category. In response to acute stress, our bodies’ sympathetic nervous system activates glands that release a host of toxic chemicals that charge fight or flee. When we’re scared, we’re not in the past, present, or future. We’re not thinking, wondering, or creating. We are instead blinded by biochemistry where anxiety, uncertainty, and fear reign.

So how do leaders create safety? Organizational schemes like furloughs and extended health care are all well and good, but there’s something more fundamental. More essential. More atavistic. And more readily available. Reassurance. Reassurance alleviates fear and restores safety. It sounds simple, just as Maslow’s hierarchy looks simple. But when we’re scared, what we most desire is to have our brows stroked while closely held and told “It will be okay.” Nothing alleviates fear more than that. Nothing makes us feel safer.

Only in the last weeks have national leaders begun to say in response to COVID-19 that everything will be fine. That we will return to our lives and relationships. That we will attend festivals and church. But it took them almost five months of frightening us with blunted facts and queasy projections before understanding that the human psyche can suffer only so much. COVID-19 will be remembered, above all things, as a failure of leadership to make us feel safe.

Let’s hope our leaders don’t forget Maslow again.

- The State of Housing in Black America - Dr. Vanessa Perry

-

Homeownership enables families to build wealth, helps stabilize communities, and has been linked to access to educational, employment opportunities, increased safety as well as physical and mental health. The market for single-family homes and their financing are key components of a strong economy; the housing market also provides employment for thousands of professionals as well as earnings for industry practitioners and returns for investors.

Despite the emphasis on this aspect of the “American Dream” in popular culture and among scholars and policymakers, Black and other minority families have faced a number of barriers to homeownership, most of which can be traced to cumulative disadvantage and structural inequalities. In the years since the 2008 crisis, homeownership opportunities for Black Americans had begun to take a promising turn. However, in early 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic very quickly began to threaten the lives, health, and economic viability of Black households across the United States.

I recently completed an in-depth research project on this important topic, as the lead author of the “2020 State of Homeownership in Black America: Challenges Facing Black Homeowners and Homebuyers During the COVID-19 Pandemic and an Agenda for Public Policy,” on behalf of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers. The report presents the current state of homeownership for Black households in the U.S., market opportunities for Black homebuyers, key demographic and economic characteristics that differentiate Black homeowners, a profile of Black mortgage loan applicants and borrowers based on mortgage underwriting criteria, and recommendations for impactful public policy interventions from federal, state and local governments, the mortgage market and the real estate industry.

I, along with several industry experts, will be discussing the report at the National Conversation on Black Homeownership at 1:00 p.m. on Tuesday, October 27, 2020.